Simmons Students Present at Boston College Conference

Posted May 2, 2022 by Johnna Purchase

Over the weekend, the Boston College History Department hosted their first annual graduate student conference entitled “Grad Student Voices.” The student leadership team possessed a simple yet bold vision – a conference for graduate students by graduate students. Especially as a student just finishing her first year of her M.A. in History, I found it refreshing to attend an history conference that uplifted graduate voices rather than relegating their voices – and the students themselves – to the corner.

Since the dual degree Archives and History program here at Simmons pairs the M.A. in History as a complement to the M.S. in Archives Management, at times I have struggled to engage with my peers as fellow historians. The dominant attitude is that we are archivists first. And while I take my role as an archivist seriously because of the authority it invests in me in determining what records make it into the archives that future historians will rely on, sometimes I just want to dive deep into the theoretical frameworks and dizzying array of possible research topics in history as a discipline. Even as I’m in the midst of grappling my way through a variety of frameworks for my final paper in “HIST 561: Decolonizing the Archive,” I still want to explore what happens when old and new methods of “doing history” collide, reform, and rise up from the ashes of their past as we historians try to understand their value in relation to present concerns and under-documented groups. Sometimes I want to tip-toe out of the very real archival practicality of Hollinger boxes, donor agreements, and outreach programming to swim in the sea of historical research. The Grad Student Voices conference at Boston College provided just such an opportunity even while reminding me of the invaluable relationship between my work as an archivist and the work of historians.

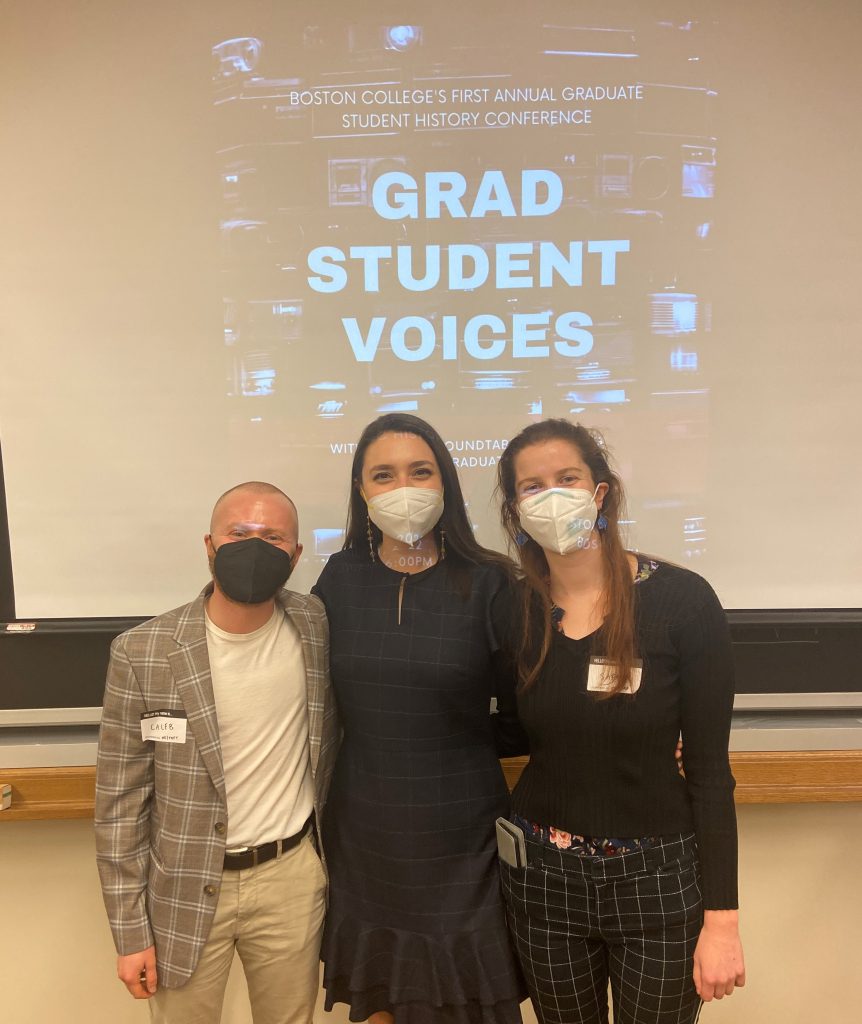

Although presenters traveled from all across New England to attend, the Boston locals gave an impressive showing at the conference. Simmons itself had three presenters chosen. Ironically – but perhaps not so surprisingly – all three of us presented on the final panel of the day entitled “The Politics and Culture of Gender and Sexuality.”

Caleb Simone kicked off the panel with their paper “Justified Deviance: Gender, Sexuality, and Normativity in Transvestia” in Cold War America. Their study cautioned the reader against the lump-sum grouping of similar identity groups, opening up the way for understanding complexity reflective of individual experience in that historical moment rather than vis-à-vis present cultural understandings.

Sarah Shepherd presented “ ‘Joking Aside, He Made a Peach of a Bride!’ : Gender Play in Early Twentieth Century West Virginia” which examined how same-sex mock weddings became community-building events. These active subversions of gender norms were rendered socially acceptable due to their function as charity events.

I presented the paper “Feminist Erasure and Myopic Views: A Historiography of Direct Female Political Engagement in Post-Independence India’s Early Parliaments.” My work demonstrated how the dismissive attitudes of feminist historians in the 1980s and 1990s effectively silenced any research on the political engagement of women in India during the post-Independence years. However, new scholarship demonstrates how women did, in fact, meaningfully shape India’s nascent democracy through their efforts in voter registration, voting, and legislating.

Between the coffee break chats, student experience roundtable, and post-conference reception, I was filled with a sense of optimism and camaraderie. As one panelist reflected, “studying history is an incredibly optimistic endeavor.” And as another exclaimed, “we are now your people.” This, perhaps, was the most meaningful part of the conference beyond all of the great book recommendations and engaging insights from others’ research. I came to the conference thinking “my people” were the other Simmons students but left with “my people” expanded to include a circle of generous, wicked-smart historians from all across New England.